Migration Out Of Africa Left Its Mark On Jordan Valley Nearly 2 Million Years Ago

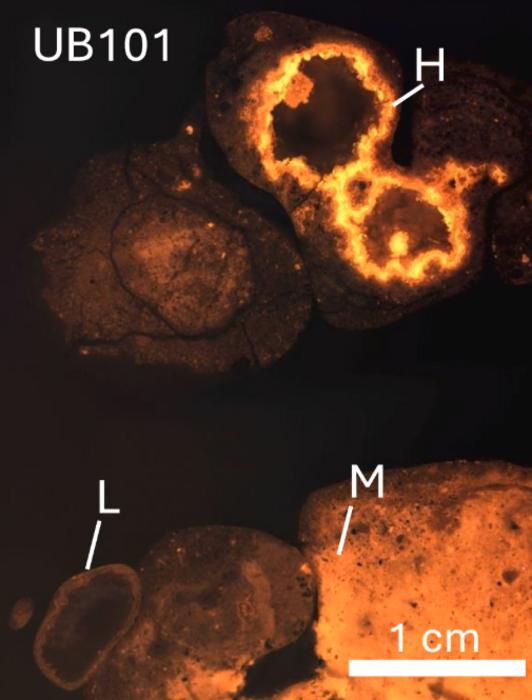

A specialized imaging technique reveals mineral layers preserved within a fossilized Melanopsis shell.

Bifacial stone from Ubeidiya Formation. Credit: Omry Barzilai.

A new study has determined that the archaeological site of ‘Ubeidiya in the Jordan Valley dates back at least 1.9 million years, pushing back evidence of early human presence in the region by hundreds of thousands of years and positioning the ‘Ubeidiya site, together with Dmanisi, Georgia, the oldest evidence of early humans outside of Africa. The discovery revises a critical moment in human evolution, indicating that ancient pioneers, equipped with a diverse array of stone tools, were established in the Levant at the dawn of our species’ global expansion.

A new study led by Prof. Ari Matmon of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Prof. Omry Barzilai from the University of Haifa, and Prof. Miriam Belmaker from the University of Tulsa provides a clearer timeline for one of the most significant prehistoric sites worldwide for the study of human evolution. By integrating three advanced dating techniques, researchers have determined that the site of ‘Ubeidiya in the Jordan Valley likely dates back to at least 1.9 million years ago. The study was published in the Quarternary Science Reviews.

This revised age suggests that ‘Ubeidiya is among the oldest known sites of early humans outside of Africa. The ‘Ubeidiya Formation has long interested researchers because it preserves early evidence of the Acheulean culture, characterized by large bifacial stone tools found in association with rich faunal assemblages, including species of African and Asian origin, some of which are now extinct.

However, establishing the site's exact age has been a challenge for decades. For many years, most researchers estimated that ‘Ubeidiya dated to between 1.2 and 1.6 million years ago but this age was based on relative chronology. To determine the precise age range of ‘Ubeidiya, the team returned to the site and resampled it using a battery of novel dating techniques, each offering a different way of probing the deep past.

One method, known as cosmogenic isotope burial dating, measures rare isotopes created when cosmic rays strike rocks at the Earth’s surface. Once those rocks are buried, the isotopes begin to decay at predictable rates, effectively starting a geological clock that reveals how long they have lain underground.

The scientists also examined traces of Earth’s ancient magnetic field preserved in the site’s lake sediments. As sediments settle, they lock in the direction of the planet’s magnetic field at that moment. By matching these magnetic signatures to known reversals in Earth’s history, the researchers determined that the layers formed during the Matuyama Chron, a period that began more than two million years ago.

Finally, the team analyzed fossilized Melanopsis shells, freshwater snails embedded in the sediment, using uranium-lead dating to establish a minimum age for the layers in which the stone tools were discovered.

Altogether, the results converged on a significantly earlier date than previously assumed. The findings indicate that the ‘Ubeidiya site is at least one million nine hundred thousand years old, representing a major shift in our understanding of early human history. This new timeline suggests that ‘Ubeidiya is roughly the same age as the well-acknowledged Dmanisi site in Georgia, which means our ancestors were spreading across different regions at a similar time. It also suggests that two different technologies of making stone tools, the simpler Oldowan tradition and the more advanced Acheulean, migrated at the same time from Africa by the different groups of hominins as they moved into new territories.

The study also addressed a major scientific hurdle: the initial isotope readings suggested the rocks were 3 million years old, which contradicted paleomagnetic, paleontological, geological and archaeological evidence. The researchers addressed this hurdle by demonstrating that the sediments containing human remains have a long history of recycling within the Dead Sea rift and along its margins.

"The exposure-burial history that emerges from the model implies recycling of sediments previously deposited and buried in the rift valley... and then redeposited along the ‘Ubeidiya paleo lake shoreline."