Biden’s Gulf Rapprochement Offers a Half-Baked Diplomatic Ballet

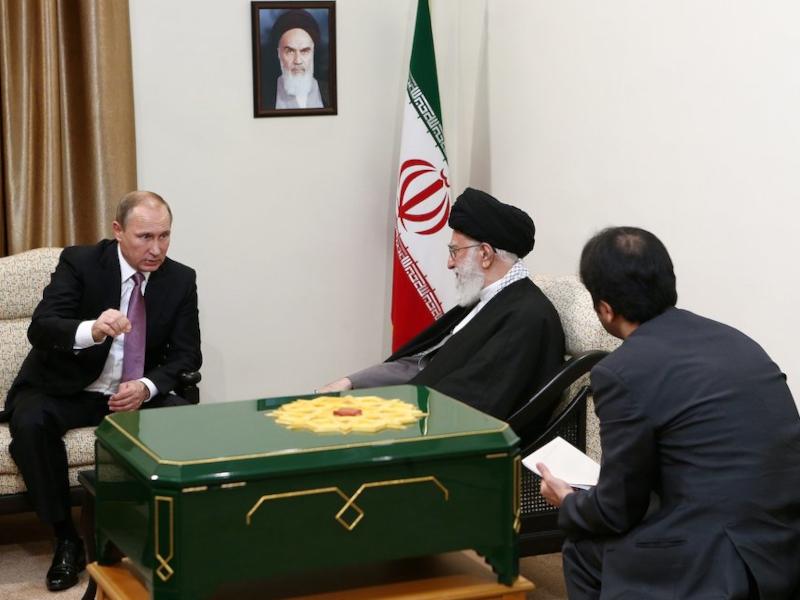

The empowerment of Tehran seven years ago allowed it to further suppress its population, expand its strategic weaponry, and maintain its nuclear program.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA aka the Obama Iran Deal) unleashed several disastrous effects in the Mideast, on US Foreign Policy, and even on American domestic politics.

But one area, the signing of the JCPOA in 2015 and the subsequent transfer of dozens of billions of dollars to the ayatollah's regime, caused direct damage to relationships between the United States and its closest allies in the Mideast—Israel, and the Arab Coalition.

Indeed, as this writer observed previously, the empowerment of Tehran seven years ago allowed its leaders to further suppress its own population, expand its strategic weaponry systems, including ballistic missiles; maintain its nuclear program despite the talks; reinforce the control by Iran-backed militias of at least four Arab countries; and provided room for sharper threats against Israel, from the north by Hezbollah, and from the southeast by Hamas.

America’s allies in the region, Arabs and Israelis alike, have suffered the unleashing of Iran’s seemingly unstoppable menaces against their countries for more than a decade —with a notable exception of just two years when the Trump administration withdrew from the Iran Deal and designated the IRCG as a terror entity.

But the return of the Iran Deal-first policy in February 2021 signaled a renewed tension with the region’s allies.

The Biden administration widened the gap between the two sides through a cascade of steps: Removing the pro-Iran Houthis from the terror list, pressuring the Saudis and Emiratis to refrain from conducting a military campaign in Yemen, slow-walking weapons to the governments of the Arab Coalition, asking the Israelis to refrain from strikes inside Iran, trying to delist the IRCG, opening the financial valves to Iran even before a deal is signed, and—well, the list is very long.

But the bottom line is that the administration’s rapid return to the policies of the Obama years triggered a distancing from America’s partners in the region. And that gap was growing.

Had the war in Ukraine not forced Washington to recalibrate its moves in the region, the distance between the US and its Mideast and North African (MENA) regional allies would have deepened and widened to chasm proportions.

What happened?

As the Russians rolled into Ukraine, Western sanctions on Moscow prompted the Kremlin to cut off energy from those in Europe who preached escalation with Russia.

The crisis became global, and the U.S. had to assist its NATO allies as they fended for their economic well-being.

The Biden administration realized it had to assume leadership responsibilities, find other suppliers of oil and gas for world markets while also maintaining a cohesive pro-Western coalition to meet these growing challenges.

Two schools of thought emerged within the administration’s spheres of foreign policy:

One, embodied mostly by the strongest proponents of the Iran Deal, advised accelerating the process of rejoining the JCPOA and relying on Iran and Venezuela’s cheaper energy markets while at the same time accepting partnerships with far radical regimes.

But this option was highly risky.

The Iranians started adding new conditions that would have made the administration look weak, especially in a midterm election year.

And the Biden team would have been sucked into a spiral of concessions to Tehran and its axis that would have forced U.S. allies in the region to jump ship into other alliances — or at minimum downgrade their special relations with Washington (symbolized by the refusal of Saudi and Emirati leaders to take the calls of President Biden).

The American public wouldn’t have understood how America’s top allies in the region, including Israel, had become sidelined while terror regimes were upgraded.

That adventure did not fly.

The second school of thought, found in Congress, especially within the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the Pentagon, and some quarters of the State Department, advised the opposite: Break the ice with the Arabs (particularly Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt), bring in Qatar, applaud the Abraham Accords, revitalize the U.S.-Israeli partnership, and get tougher on Iran.

Though difficult to accomplish against eight years of Obama policy and 18 months of the Biden extension, an engagement team directed by the White House was successful in launching a ”demi rapprochement” via a presidential tour that included Saudi Arabia, a summit with Arab leaders, and a high profile visit to Israel.

The goal is to mend fences between the Biden White House and those leaders in the region, restart trust between the two sides, and of course, convince the Gulf to assist in an oil and gas ”rescue.”

Why a demi rapprochement—and not a full one?

Because the region is still suspicious that this is only an emergency move by the US before they turn around and sign the Iran Deal—abandoning them again after the Ukraine conflict is settled.

Both sides are accepting the “truce” and the good initiatives and will send signs of friendship, but more has to be done to insure the rapprochement is truly heading toward a permanent re-bridging of relationships and not simply a half-baked diplomatic ballet.

Both sides, America and its regional allies, at least the peoples therein, are natural allies. The governments of these peoples, then, must find a way to achieve the will of their citizens on both sides of the ocean and on opposite sides of the world.

Dr. Walid Phares is a professor, Mideast expert, and the author of several books, including Future Jihad and The Lost Spring. This article is reprinted from Newsmax with the permission of Dr. Phares.